THE FUTURE IS NOW

- Filter

Fluxus and Southeast Asian Art

Author

Roy NgBiography

Roy Ng is a Curatorial Assistant from National Gallery Singapore. His art historical research focuses on photography, aesthetics, and post-/de-coloniality, but recent preoccupations also include ideas surrounding the “relational” in Southeast Asian art.

The following essay contains an image with nudity. Discretion is advised.

I bet there are still many new openings and loopholes in art history [...] which are being overlooked right now by millions of young people who complain that everything has already been done, so that they cannot do new breakthroughs. However, the history of the world says that we don’t win the games, but we change the rules of the games.

— Nam June Paik, 19921

In an attempt to eradicate “the boundaries between so-called high and low culture,” as well as the arbitrary distinction between the artist as an “active” producer and the viewer as a “passive” consumer, Fluxus artists such as Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman and Joseph Beuys sought to move art’s main obligation towards a deeper engagement with human spontaneity and everyday life.2 By rejecting the elitism of commodity culture in the art world, Fluxus aimed to form an “alternative distribution mechanism” with a loosely knit group of activities, ranging from gadget-based games to instrumental performances. The movement itself is political: Fluxus stood by its critique of capitalism and consumerism, and sought to question the system’s “mesmerizing totality and numbing continuity.”3 Curiously, these same concerns undergirded the transformation of art into a more relational form, with an aesthetic which, according to curator Nicholas Bourriaud, fosters a more radical, participatory involvement with the social reality in which we live.4 We see an interesting resonance in the artistic strategies adopted by Southeast Asian contemporary artists, including Tang Da Wu, Josef Ng and Rirkrit Tiravanija; artists who were inspired by and engaged in art that were characterized by a sense of spontaneity, an ethos of anti-consumerism and a spirit of communal action promoted by Fluxus. This then begs a few questions: What was Fluxus like in the 1960s and 1970s? What are the legacies of Fluxus that we see today? Are there any links between Fluxus and the experimental and relational approaches of Southeast Asian art?

I. Fluxus: Experiments, Experiences, the Everyday

Let us first consider Originale: an avant-garde, multi-textual music theatre event held at the Theater am Dom at Cologne in 1961. In it, Paik performed the works Simple, Zen for Head and Etude Platonique No. 3, each piece rendered with the sheer volatility of a chance event, spontaneously revealing itself based on a “score” of objects and actions. In one performance, he threw beans towards the ceiling above the audience, only to hide his tearful face in shame behind a roll of paper, which he slowly unfurled in breathless silence. In another part of the performance, Paik switched on two tape recorders playing a montage of radio news, women’s screams, children’s laughter, and distorted fragments of classical music and electronic sounds, before walking towards a stage ramp, emptying a tube of shaving cream, a bag of flour, and a sack of rice onto his head and over his dark suit down to his feet. He then jumped into a tub filled with water, coming out soaking wet, and then pounded his head onto a piano keyboard.5

In a similar performance at the Atelier Mary Baumeister in Cologne the previous year, the young Paik performed a notorious work titled Etude for Piano Forte, which he began by playing a composition by Chopin before brutally attacking the piano, then turning his aggression onto the most celebrated members of the audience: Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage and David Tudor. He snipped Cage’s tie in half, cut his shirt with a pair of scissors, and doused a bottle of shampoo over his and Tudor’s heads.6 “Not for you,” Paik remarked to Stockhausen.7 Standing firmly on the fringes of an art world tainted by consumerism and the prevalence of commercial exchange between the artist-producer and viewer-consumer, Fluxus artists like Paik created new spaces and communicative circuits in which art could redeem itself as a mode of authentic expression and social relations.

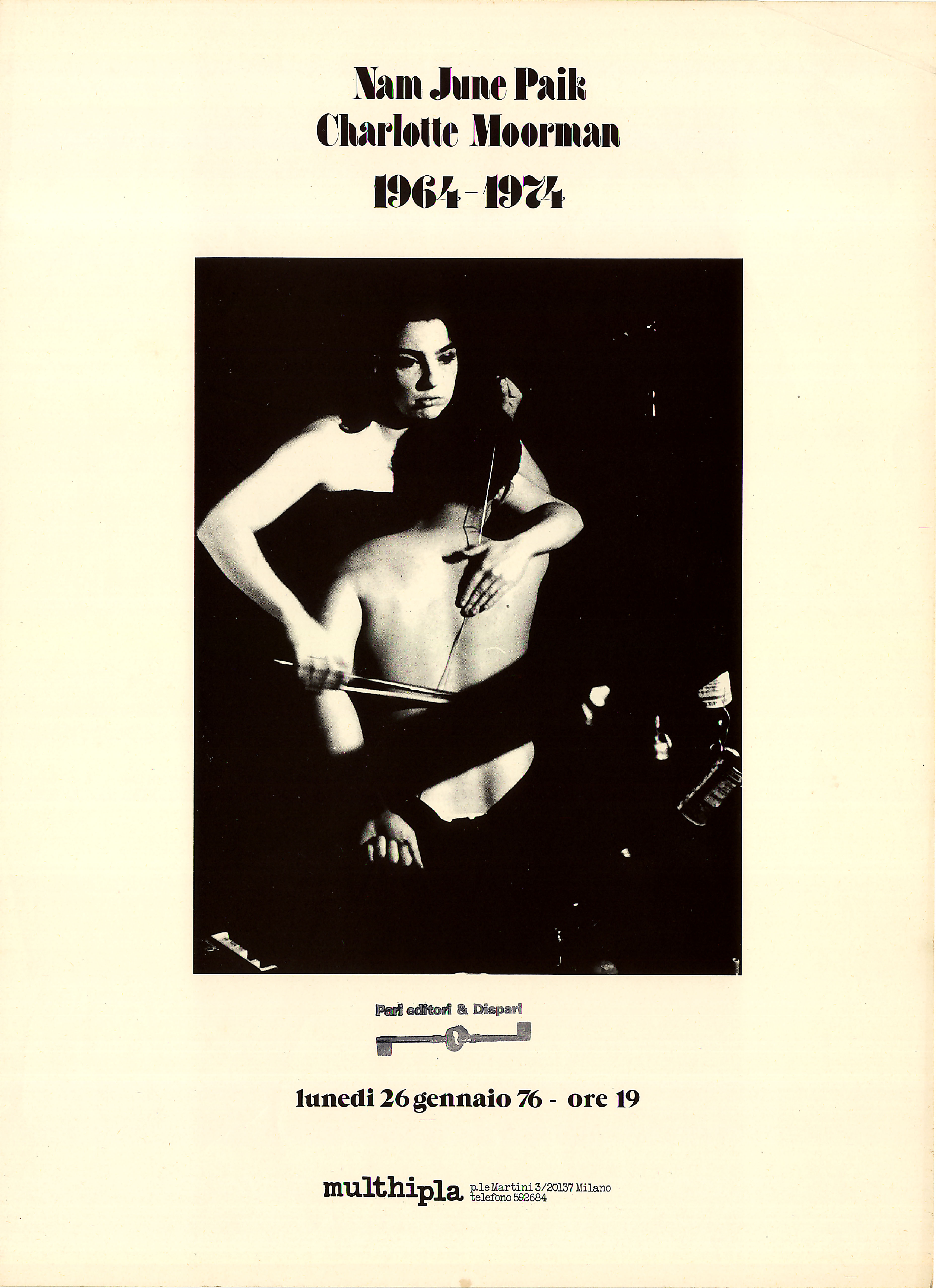

This relational aspect can also be seen in Human Cello, a collaborative performance by Paik and Moorman at New York’s Café au Go Go in 1965, re-enacted here for WNET-TV/Channel 13 Studio, New York, in 1971 (fig. 1). In what appears to be an attempt to detach, or in Fluxus terms, de-subjectivize art from the old dynamics of artist and viewer, Moorman began by executing a rendition of Cage’s 26’1.1499” for a String Player on the cello for a few minutes, before deciding offhand to play the same piece on Paik’s body, which steps in as a surrogate for the instrument.8 She pantomimes briefly around the “objectified” man as he crouches beside her, holding a string taut across his back, only to be discarded eventually by the cellist as she moves on to enact the same motion on a military practice bomb to an enraptured audience.

As Moorman spontaneously shuffles across the multiple apparatuses she uses during the performance, the formulaic identity of the artist is displaced by the overwhelming intent to violate the audience through a transgression of habitual thinking. We see an instance of what feminist theorist Karen Barad terms “intra-action”; where participants—both artists and audience—are implicated by the “enacted relationships in an ensemble” and become complicit in “[effecting] an agential cut between [the] ‘subject’ and ‘object.’”9 Moorman and Paik’s performance of Cage’s score is thus contingent not only on the dynamics of use and instrumentalisation, but also on the interpretive freedom of everyone within the space to comprehend in their own way the shifting configurations of objects, subjects and equipment. In this regard, even as the Fluxus artists assert “a figurative coauthorship” through their constant re-invention of the score, they remain merely as conduits or vessels for a form of art that can only be fully realised through a new, radical and subjective perception of reality amongst the audience.10

It is from this “non-hierarchical density of experience” that Fluxus significantly transforms the framing of art into a series of everyday phenomena, the kind that presides over the practice of art in the contemporary world.11 Just as the indeterminacy of Fluxus events subverts the artificial division between the artist and viewer, they too dismantle the pretensions surrounding the cult of the artist through the striking use of what American artist Dick Higgins would coin “intermedia.”12 Through “intermedia,” elements of poetry, music, dance and brush painting combine into a single composition and, with these new genres between genres, blur the boundaries between art, media and mass entertainment. Where the work of art was previously conceived as “complete” only after its production, the intermedial confluence of language, sound, image and bodily presence in these Fluxus works shifts the focus of artistic creation towards an open-ended—perhaps even deliberately incomplete—state reflective of quotidian social and political realities. Through these works, Fluxus artists are not merely performers, but facilitators within the social matrix formed by the work. Likewise, the audience—entangled as individuals within a complex system—can participate, collaborate and imagine new ways of living and interacting with one another.13 The shared experience of a community in flux lends the work a unique dynamism that is cohesive yet unbounded within a singular artistic objective.14 Through the use of intermedia and their “compression of shared experience, form, and content,” the Fluxus work emerges as a site of engagement and contestation where new ideas emerge—ideas on how reality can be reconceived, reconstituted and reconstructed.15

II. Southeast Asia, post-Fluxus

With multinational capital extending its reach as a global hegemonic force at the turn of the century, one might concede that the world may have more recently lost its original revolutionary purchase. And yet the subversive strategies of Fluxus have not only survived, but thrived within the realm of contemporary art. Even in Southeast Asia, we see a diverse set of performance works emerge from the 1980s to 2000s, drawing their legacies from Fluxus and its demand for more radically experimental and relational forms of art. Here, Fluxus manifests in its manifold forms, reflecting the plurality and diversity of Southeast Asia. The sheer complexity of this region confounds any attempt to produce a comprehensive survey of prevailing models of performance and relational art, but perhaps it is through the lens of Fluxus that we could see parallels, semblances and equivalences in how contemporary art in Southeast Asia may be vested in a similar sense of spontaneity, agency and inclusivity.16

Fluxus’s strategies, for example, persist in Singaporean artist Tang Da Wu’s live performances. Art, for him, was not an autonomous or self-referential thing, but an active engagement with “everyday life.”17 Drawing inspiration from the conceptual framework of the German Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys, Tang’s public performance took on a similar ritualistic quality, imbued with his conviction in the power of human creativity between both the performer and the audience. Tang’s works are often embodied—in a most literal way—through a set of ludic processes or “play,” where the artist is free to interact with audiences through the communicative circuits established from within and beyond the work.18 One of Tang’s seminal works, They Poach the Rhino, Chop Off His Horn and Make This Drink (fig. 2), exemplifies these processes. Straits Times journalist T. Sasitharan, who was one of the attendees of Tang’s performance event, offers a meticulous account that provides some insight into the work’s theatrical and eclectic presence before the audience:

A rhinoceros, constructed of wire-mesh and paper, butchered for its horn was laid out in the centre. A white axe lay beside it. Around these objects, in a continuous concentric circle, was a formation of bottles, containing a medicinal drink. […] At first the audience skirted it, grating it the status and sanctity of at objects. People merely looked from a distance. Then slowly they began relating to it, picking up bottles and reading labels.19

Half an hour later than advertised, Tang re-enters the space. According to Sasitharan: “Using a hand puppet of a small furry mammal, he brought us through the process of confronting the horror and grieving the loss [of the rhino].”20 Tang makes his way within the spiralling sets of bottles, before suddenly pushing the axe aside to create what appeared to be an altar: “The grief was expressed as Chinese ritual mourning, with red candles, joss-paper and joss-sticks. Even though we were all responsible, Chinese culture, in perpetuating the [medicinal] myth, was particularly culpable.”21 Here, he nuances and re-appropriates his presentation in relation to the audience’s response—exerting not merely what is already a charismatic grip on the audience members, but allowing them to engage in a ritualistic commemoration of the animal. Much like the practices of ancestral worship common in Singapore, we see here a personal and intimate relationship with the demised subject in question. The art object, through They Poach the Rhino, is de-materialized and localized – the essence of the work (and Tang’s critique) is embedded in a network of relations specific to the site, duration, and context of the performance. As Tang describes in an interview in 2001:

Yes, all thinking, all planning, they are not a performance yet, until you [have] reached your audience. There is a very special kind of energy coming from the audience. Your performance comes alive and reach[es] its highest point.22

Far from being reduced as a mere commodity, art now exists in place and as participation: the on-site audience collaborates in the poetic process of meaning-making, connecting the white cube of the art venue with the “warp and woof of the everyday” in Singapore.23 What emerges here is indeed a resonance, and perhaps even a borrowing, from Fluxus’s conceptual models, but rather than simply harkening back to the latter’s Euro-American origins, Tang’s work grounds itself as being rooted in local and transnational Chinese customs.24 Tang creates, according to C.J.W.-L. Wee, an internal critique of what it means to be Chinese, questioning his own positionality as a Chinese-educated artist, and asking the audience whether they should adopt certain traditions unquestioningly.25 To use Thai art historian and curator Apinan Poshyananda’s words, Tang’s oeuvre “received attention for their attempt to redefine conceptualism in terms of local/global contextualizations;” concepts surrounding “anti-commodification,” “relational aesthetics,” and “the everyday” in Fluxus is reinvented in Tang’s own “re-examin[ing of] Chinese traditions and myths surrounding the eating of animal parts as an aphrodisiac.”26 Tang’s performance attempted to re-orient the viewer’s relationship to art by questioning the autonomous values placed on these objects, where the inherent values are ultimately socially constructed and culturally derived.

Another example of such localization is Josef Ng’s 1994 performance Brother Cane (fig. 3) as part of a 12-hour New Year’s Eve programme organised by 5th Passage and The Artists Village, the latter a contemporary art group in Singapore established by Tang himself. This much-discussed performance, which expresses Ng’s opposition to Singapore’s entrapment of gay cruisers, is most remembered for the artist exposing his pubic hair and stubbing a cigarette out on his arm. As the Singaporean writer Ng Yi-Sheng recalls:

Few LGBT artists in Singapore dare to venture into this territory, but Josef did, with his gasp-worthy ministrations of scissors, cigarette, tofu and cane. This was “protest art”, he proclaimed to The New Paper when their reporter came to view the show, and the same statement was broadcast on page one, though in a smaller font than the eye-catching “PUB(L)IC PROTEST” headline.27

Ng, to quote artist Ray Langenbach who also attended the event, “produced a state of catharsis in the audience—through the performance, a social trauma and schism in the community, the transgression, arrest, punishment, and public exposure of the twelve men were ritually remembered and redressed.”28 Just as Fluxus replaced the one-way relationship between the artist and audience with a more two-way consciousness, works like Ng’s direct the form of art towards what Bourriaud terms “a relational property,” tied to the “perpetual transactions” of inter-subjectivity between people yearning to confront systems of state surveillance and control.29

This fusion between art and life is even more pertinent if we consider Singapore’s National Arts Council’s response to Ng’s work – a response which amplified the existing tensions between performance art, the state, the media and the public. Publicly branding the performance as being “vulgar and completely distasteful,” NAC banned the funding of 5th Passage and performance art in Singapore for a decade, until 2004.30 Details of the performance and its legacies have also been well documented by a number of sources including by curator Louis Ho and artist Loo Zihan, the latter in a performance event and installation at The Substation Gallery in Singapore in December 2012. Through Loo’s re-enactment and display of archival materials surrounding Cane, the work becomes a document-engaged performance piece–incorporating eyewitness accounts by Langenbach along with other visual and oral records. To quote contemporary artist Bruce Quek:

[I]f the overall accumulation and circulation of documents relating to Brother Cane, in all of their disparate, branching threads, constitute mycelia, Cane would then be a sporocarp – a fruiting body, which emerges for the dispersal of informational and performative spores.31

Brother Cane and its reconstructions are explicitly mediated and decidedly enmeshed in a web of stories, deferrals, interventions, and regulations. As Loo notes: “[…] presenting all these accounts is a way of emphasizing the fragmented nature of memory, the constant repetition drowning out the original piece… A reminder that there is no definitive representation of Brother Cane that will do it justice, and it is not the intention of my piece to do so.”32 Here, the piece is deliberately positioned within a matrix of interconnected power structures and narratives where, although premised on a pre-ordained script, expands beyond the confines of the New Year’s Eve programme to involve various local audiences and authorities. What is at stake is not merely the actual performance itself, but the “fragmented” memory of the piece, constituted by a patchwork of responses, writings, and documents – all of which sets the foundation for further contestation.33

In this way, the corporeal figure in Brother Cane alludes to more than just the physical figure of Ng (or Loo). The exposed body, as disruptive and deviant as it may have seemed, reveals a body politic; the aggregate body of subject-citizenry comes face to face with its sheer performativity and long-held obligation to maintain a semblance of social order, propriety and respectability.34 Where prescriptions of the law governing nudity establishes a means to which the citizen-subject is constructed (as a compliant, clothes-wearing individual), Brother Cane subverts these standards of public decency and order, and reveals them as being rooted not simply in law, but also in a communal body. They are, to use Judith Butler’s theory on subjectivity, shaped by the required performativity of subjects whilst aligning themselves with hegemonic discourses, now comprehended as the ‘self’.35 By repeating the performance, practitioners like Loo render the body identifiable by means of citation and (re)citation, drawing attention to the power of state legislation and enforcement, and re-inscribing it to that of the collective. Herein lies the diffusive power of Ng’s work where, beyond the physical space of the performance, all parties engaging in the topic of Brother Cane are forced to grapple with the deeply held assumptions undergirding their role as socialised, functioning organs of society and the state.

One final example of this relational approach may be found in Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work Pad Thai, first held in 1990 at the Paula Allen Gallery in New York. Unlike Tang and Ng, Tiravanija operated on a much larger, global arena—translating Thai cuisine and notions of conviviality to international art venues. Rejecting traditional art objects, Tiravanija attempts to offer a counterweight to the regressive effects of consumer society through the socialising potential of a shared meal. Here, he cooks and serves food for visitors in the exhibition, allowing audiences—now elevated as participants—to draw on culturally specific acts such as the culinary practice of cooking pad thai within a communal setting. Visitors engaging in these acts are also invited to engage in “public debate and ad hoc discussions in the convivial atmosphere of shared food,” congregating around the table as they prepare the meals, eat and wash up.36 The spontaneous acts of cooking, dining, and striking up conversations become a light-hearted critique of traditional art and the associated preconceptions of art as an autonomous object.37

In a similar vein, Tiravanija’s Untitled (Curry for the Soul of the Forgotten) depicts curry being made in a bronze brazier, which is then incorporated as an installation documenting the act of cooking and sharing Thai curry (fig. 4). As German art historian and curator Thomas Kellein describes:

Tiravanija’s revolution lies in the fact that his cooking is transforming crucial questions, issues, and formats of current art production – for instance, the exclusivity of art history, the private agendas of collectors, or very different artists’ attitudes (which, by the way, he can easily accept) – to create a kind of wordlessness, a nirvana of everyday aesthetics. Just because he cooks, it does not necessarily translate into art. Rather, it arouses an easily ignored, primordial, yet ubiquitous culture, linked to individual and collective memory and desire.38

As the visitors cook on-site, Tiravanija facilitates a discussion on a range of topics from sustainable nutrition to food cultures. More than just a “gastronomic service,” the meal-time gathering functioned as a hospitable gesture—a place within which the means of interaction and social exchange transform into a self-sufficient community sustained by genuine human relations and togetherness.39 We are now made aware of the deeper existential questions underlying each ingredient, each act of cooking, each olfactory sensation—the distribution of food, the assimilation of cultures, the call for a more organic and casual network of exchange and cooperation. Tiravanija’s work resonates with anthropologist James Clifford’s observation that, far from living in a homogenous world, human relations are inherently “ambiguous” and “multivocal,” where a “rhizome agglomerate of subcultures” intermingle and interfere with one another. The artist, as a function of these relations, are not producers of objects, but instead mediators for processes and dialogues that can only be experienced in person and as persons.

In this regard, Pad Thai and Untitled (Curry for the Soul of the Forgotten) are reminiscent of the conceptual principles of a Fluxus event, insofar as they operate based on a social matrix of participants who, by collaborating in imagining a more “humanised” vision of reality, carve out spaces that are free from the isolation of automation and digitised communication. Instead of working towards creating imaginary and utopian worlds, the role of the work is radically rooted in the ways of living within the current plane of existence.40 One may consider a quote by Bourriaud, who recognizes Rirkrit’s works as exemplars of relational aesthetics: “It seems more pressing to invent possible relations with our neighbours in the present than to bet on happier tomorrows.”41 This recalls the approach proclaimed by Beuys in the sense of a social sculpture – and indeed, Fluxus’s strategies continue to echo in these more recent fields, their reverberations manifesting in ways that are both specific and universal to the artist’s cultural background.

By drawing attention to two distinctly Thai dishes, pad thai and thai curry, Tiravaija asserts the works’ own foreignness, examining notions of national, diasporic, and personal identity. The artist, being ethnically Thai but born in Argentina and now in the US, regards himself as an outsider, and this too is reflected in the dishes: “Thai food wasn’t something that everyone had experienced. It was still something on the edge, something exotic perhaps; it definitely challenged your normal sense of food.”42 Using pad thai as a medium, the artist points to not just his heritage, but also its constructed nature; the dish, although originating from China, was proclaimed by Prime Minister Phibunsongkhram in 1940 as the national dish in order to strengthen the identity and new westernized outlook of the modern Siamese state.43 Here, the dishes become a means towards self-fashioning, much in line with what historian Eric Hobsbawm regards as the “invented traditions” of countries that sought to instil a sense of patriotism and national belonging through a unified cultural symbol.44 Through Pad Thai and Curry for the Soul, Tiravanija raises these questions of belonging in the globalized context of the contemporary world, offering a space for genuine interpersonal exchange untainted by the sterility of consumer culture.

III. Conclusion

If, according to philosopher Guy Debord, the nature of social relations between people are increasingly mediated by mass media under the sway of advanced capitalism and other systems of control, one may consider the redemptive potential of Fluxus in offering an authentic vision of art that liberates everyday life from this oppressive spectacle.45 By asserting the primacy of immediate experience, Fluxus seeks to reduce the arbitrary divide between the artist and the viewer, empowering the latter as a participant of a flexible intermedial space within which they can exercise their creativity and play a role in the collaborative re-imagining of everyday reality. It is this subverting force that Fluxus not only spurs a more experimental and relational mode of art in Southeast Asia, but also lays the foundation for its prime objective: to forge a closer union between the realms of art, society and everyday life.

- From an undated typescript in the collection of the Nam June Paik Estate. Edith Decker-Phillips identifies the text as being from spring 1992. Originally published in German, in a translation by Decker-Phillipe, in Nam June Paik: Niederschriften eines Kulturnomaden [Nam June Paik: Notes of a Cultural Nomad] (Cologne: DuMont, 1992), 194–8. English text reviewed by Alan Marlis.

- Owen Smith, “Avant-gardism and the Fluxus Project,” Performance Research 7, no. 3 (2002): 8; Natasha Lushetich, “Ludus Populi: The Practice of Nonsense,” Theatre Journal 63, no. 1 (March 2011): 23–4.

- Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, “Robert Watts: Animate Objects—Inanimate Subjects,” in Experiments in the Everyday: Allen Kaprow and Robert Watts—Events, Objects, Documents, eds. Benjamin H.D. Buchloh & Judith F. Rodenbeck (New York: Miriam and Ira. D. Wallach Art Gallery, 1999), 22; Timothy Bewes, Reification, or, The Anxiety of Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 2002), 267.

- Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance, Fronza Woods & Mathieu Copeland (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002), 13.

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The Worlds of Nam June Paik (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000), 30.

- Sook-Kyung Lee & Susanne Rennert, Nam June Paik (London: Tate Publishing, 2011), 29–30.

- Ibid.

- Moorman describes her work in Austin Lary, “Is New Music Being Used for Political or Social Ends?” Source: Music of the Avant Garde 3, no. 2 (July 1969): 90; also see Holly Rogers, Sounding the Gallery: Video and the Rise of Art Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 174–5; William Fetterman, John Cage’s Theatre Pieces: Notations and Performance (New York: Routledge, 2010), 114.

- Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 139–40.

- Benjamin Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 171.

- Owen F. Smith, Fluxus: The History of an Attitude (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, 1998), 10.

- Dick Higgins, “Intermedia,” Something Else Newsletter 1, no.1 (February 1966), reprinted in Dick Higgins, Horizons: Poetics and Theory of the Intermedia (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 18–21.

- David T. Doris, “Zen Vaudeville: A Medi(t)ation in the Margins of Fluxus,” in The Fluxus Reader, ed. Ken Friedman (Chichester: Wiley, 1998), 105.

- Chris Thompson, Felt: Fluxus, Joseph Beuys, and the Dalai Lama (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2011), 67.

- Hannah Higgins, “Fluxus Fortuna,” in Friedman, op. cit., 57; Hannah Higgins, The Fluxus Experience (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003),58.

- Joan Kee, “Introduction – Contemporary Southeast Asian Art: The Right Kind of Trouble,” Third Text 25, no.4 (2011): 374–5.

- Tang Da Wu’s interview with C.J.W.-L. Wee in Wee, “Tang Da Wu and Contemporary Art in Singapore,” in The Artists Village: 20 Years On (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum and The Artists Village), 16.

- [Ibid., 16–7.

- T. Sasitharan, “Grim Tale of the Hornless Rhino,” The Straits Times, 15 May 1989, 3.

- Sasitharan, op. cit., 3.

- Ibid.

- “Performance Art Project: Interview with Tang Da Wu on March 24, 2001 by John Low,” in Open Ends – A Documentation Exhibition of Performance Art in Singapore (Singapore: The Substation, 2001), unpaginated.

- Wee, op. cit., 16

- Wee, op. cit., 17.

- Ibid.

- The Substation, Tang Da Wu: A Perspective on the Artist: Photographs, Videos and Texts of Singapore Performances (1979 to 1999), handout (Singapore: The Substation, 1999); Lucy Davis, “Of Commodities and Kings: Tang Da Wu’s Play with Psycho-Geography and Public Memory,” Art AsiaPacific 25 (2000): 62–7.

- Ng Yi-Sheng, “Becoming Josef,” in Louis Ho & Loo Zihan, eds., Archiving Cane: A Durational Performance and installation by Loo Zihan at The Substation Gallery, Singapore (7 December 2012 – 16 December 2012), 14; “Pub(l)ic Protest,” The New Paper, 3 January 1994, 1.

- Ray Langenbach, ‘Leigong Da Doufu: Looking Back at “Brother Cane,”’ in Looking at Culture, eds. Sanjay Krishnan et al (Singapore: Chung Printing, 1996), 123 –36, see in particular 127.

- Bourriaud, op. cit., 22.

- ”Such Acts Debase Art: NAC,” The New Paper, 5 January 1994, 14;”Govt Acts Against 5th Passage over Performance Art,” The Straits Times, 22 January 1994, 6.

- Bruce Quek, “Real Meat,” in Ho & Loo, Archiving Cane, 87.

- Loo Zihan, in a personal email to Louis Ho, October 23, 2012, in Louis Ho, “Loo Zihan and the Body Confessional,” in Ho & Loo, Archiving Cane, 95

- Ho, “Loo Zihan,” 99-100

- Ho, op. cit., 102.

- Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (New York & London: Routledge, 1993), 12

- Felix Bröcker, “Food as a Medium Between Art and Cuisine: Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Gastronomic Installations,” in Culinary Turn: Aesthetic Practice of Cookery, eds. Nicolaj van der Meulen & Jörg Wiese (Bielefield: Transcript Verlag, 2017), 175.

- Ibid.

- Thomas Kellein, “Essay,” in Cook Book, ed. Thomas Kellein (Bangkok: River Books, 2010), 134. This recipe book accompanied the exhibition at Kunsthalle Bielefeld from 11 July –10 October 2010.

- Iris Därmann & Harald Lemke, Die Tischgesellschaft. Philosophische und kulterwissenschaftliche Annäherungen [The Dinner Party: Approaches in Philosophical and Cultural Studies] (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2008), cited in Bröcker, op. cit., 176.

- Bourriaud, op. cit. 13.

- Bourriaud, op. cit. 45.

- Daniel Birnbaum and Rirkrit Tiravanija, “Rirkrit Tiravanija: Meaning Is Use,” Log 34 (2015), 163.

- Alexandra Greeley, “Finding Pad Thai,” Gastronomia, 9, 1 (2009), 78-82

- Eric Hobsbawm, “Introduction: Inventing Traditions,” in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 1.

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb (Canberra: Hobgoblin Press, 2002), 7–8.