THE FUTURE IS NOW

- Filter

Different Frequencies: Between Abstraction and Technology in Southeast Asia

Author

Clarissa ChikiamcoBiography

Clarissa Chikiamco is a curator at National Gallery Singapore. Her past exhibitions at the Gallery include Between Declarations and Dreams: Art of Southeast Asia since the 19th Century, A Fact Has No Appearance: Art Beyond the Object, Between Worlds: Raden Saleh and Juan Luna and Chua Mia Tee: Directing the Real. She was the acquisition curator for the Ateneo Art Gallery’s inaugural collection of video art in 2012 and is currently a PhD candidate in Film Studies at King’s College London.

In 1963, Nam June Paik held his landmark exhibition Exposition of Music—Electronic Television at Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, West Germany. He manipulated television sets and transformed the imagery on their screens, seeing the artistic potential in this domestic object of technology. In his notes to the exhibition, Paik acknowledges being inspired by K.O. Götz, the German art informel painter (fig. 1)—a seemingly bizarre tribute that has been highlighted by the art historian Christine Mehring.1 In her essay “Television Art’s Abstract Starts,” Mehring asks, and answers, the question: What does an abstract artist have to do with television art? She traces Götz and Lucio Fontana’s early interest in television—images generated by the cathode ray tube and ideas of transmission—as an artistic medium.2 Yet, without access to the technology and the industry to realise their visions, both artists responded to television through the language of abstract painting instead.3

In the context of Southeast Asia, I similarly propose that precedents to artworks using technology—including but not limited to video and television—can be located in abstraction. Not coincidentally, abstraction found its footing in the region when many countries were developing and nation building. These countries aspired to modernise after the destruction of World War II and the recognition of their independence following long periods of colonisation. Through a brief analysis of the work of three artists, Lee Aguinaldo (1933–2007, Philippines), Choong Kam Kow (锺金鈎, b. 1934, Malaysia) and Lin Hsin Hsin (林欣欣, Singapore), I argue that abstract art has connections to what is usually referred to as “new media art,” or art which uses electronic media and is often considered—and treated—as a distinct and separate category of art history.4 My aim is not to tackle the subject of abstraction and technology in great depth nor provide a comprehensive survey, but to skim the surface to show that the pursuit of this trajectory in some detail is worthwhile. While artists started experimenting with actual forms of “new media” at varying moments in the region, mostly between the 1970s and the 1990s, artists were no less stimulated by technology’s prospects, even without the equipment for their creative practice.5 Preceding these experiments, artists and art critics considered abstraction as a new, contemporary mode of art practice during the post-war period of the 1950s to 1980s. Abstraction—in form, process and materials—became a fitting visual expression of technology and its intensifying presence.

I Electricity Turned Off, Television Turned Off, Mind Turned On

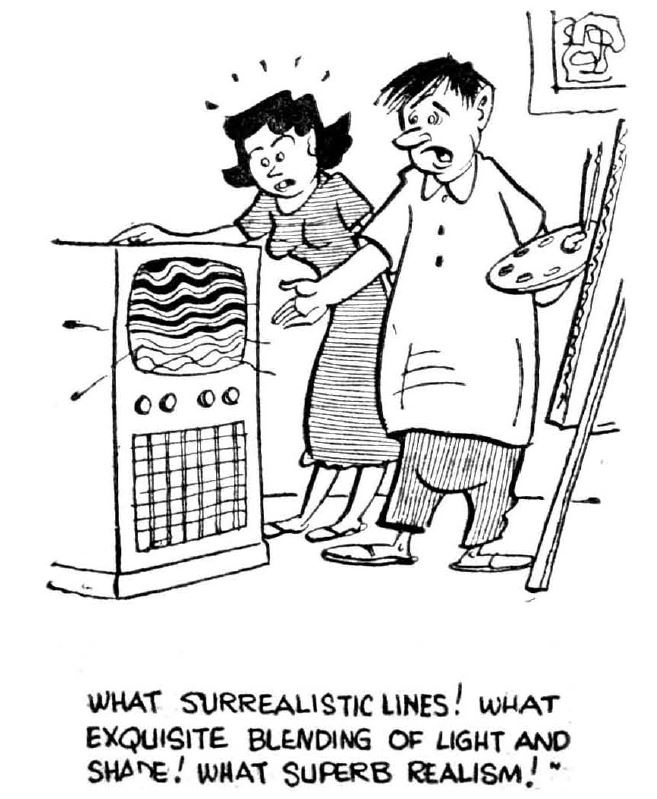

Though this essay mainly focuses on the three aforementioned artists, I begin with Liborio “Gat” Gatbonton (1914–1976), a cartoonist from the Philippines. Gat was possibly the first in the region to see television’s potential link with abstraction, even though it was through the lens of satire. Gat worked as the art director for the Manila Chronicle, wittily commenting on Philippine society in his one-liner editorial cartoons.6 A favourite subject was modern art, which was battling for acceptance in the Philippines after the war.7 Artists pitted semi-abstracted forms against the bucolic representational images that the public had become used to, while their heated debates on modern vs conservative art were published in periodicals.8 Gat got in on the action, poking fun at the seeming lack of skill in abstraction. In one such cartoon attributed to him, a painter admires the abstract lines of a television screen, much to the incredulity of his companion (fig. 2).

This linking of the television image to abstraction was also perhaps a matter of opportune timing. The cartoon was published around 1954, the year after television had arrived in the Philippines, making it the first country in Southeast Asia to access the technology.9 Television’s arrival coincided with the country’s landmark exhibition on abstraction The First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagala, held in 1953 at the then bastion of modern art: the Philippine Art Gallery.10 Though none of the works in this exhibition made any apparent connections to technology, Gat made the intuitive tongue-in-cheek observation of television’s abstract potentiality, even returning to the same theme a few years later. This time he went further: the character not merely admires but actually paints an abstract work to replicate the lines of a television screen, much to the chagrin of his scolding wife (fig. 3). Though hard to imagine with the high-definition television of today, early television was prone to displaying abstracted images due to its lower resolution, black-and-white display and potential signal interference disrupting the raster or scanning lines which compose the electronic picture.11

Though not as blunt as Gat (or his characters for that matter), abstraction drawing from technology would be picked up again surreptitiously some years later by Lee Aguinaldo, a self-taught artist who was part of the seminal 1953 exhibition of non-objective art. Initially an abstract expressionist painter, Aguinaldo began his Linear series, the body of abstract works for which he is best known, in 1965. Aguinaldo called this series “the painting of light,” with each work composed of sleek zones of radiant colour (figs. 4 and 5).12 The art critic Alice Coseteng observed, “Aguinaldo has simplified his images into mechanical and impersonal bands or zones of light-reflecting colors. Thus subtle tonal variations seem projected on the screen that is the canvas.”13

Rather than a filmic projection, television arguably offered the more compelling screen that Aguinaldo transposed in his paintings. While Coseteng does not explicitly mention television, she seems to suggest movement through a television’s curved screen when she says the works are “neither Pop nor Op […]. One seems to be looking at the Op image through expanding and contracting concave or convex lenses.”14 The Linear series also seem to refer to the televisual image made of scanning lines by its very title. In addition, the light-emitting object of television, a newer medium than film, is more reflective of the contemporaneity associated with Aguinaldo’s Linear series at that time. Emmanuel Torres, the curator and art critic, connected the Linear paintings to the latest trends in art, architecture and industrialisation.15 He added: “the rationale behind his geometric forms, graph-like and boxlike designs, straight verticals and horizontals, spacious illuminism, smooth almost factory-finish surfaces is that the imagery of the machine, of space-age technology, of mass-media packaging, is here to stay and such provides a valid stimulus for creative imagination.”16

This association with the new could be partly attributed to acrylic paint, then a new medium which Aguinaldo is credited for introducing to the Philippines with this series.16 His paintings’ polished appearance was also the result of the meticulous preparation of the plywood—not canvas—surface with several layers of gesso.18 Their façade emulated, intentionally or not, the glossy screens of electronic media. The look, the materials and Aguinaldo’s disciplined methodology made the Linear series conducive to an association with technology and its implied machinery.

This connection is further hinted at in Aguinaldo’s 1972 solo exhibition at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, for which he selected the best of his Linear works. The exhibition notes, which he may have penned himself, cryptically state: “The circumstances behind this exhibition had something to do with his plans of leaving the country ‘to study technology in the McLuhan universe.’”19 The precise link between the Linear paintings on show and the artist’s interest in technology and the renowned media theorist Marshall McLuhan however, was left to the audience to decipher. In the early 1960s, McLuhan saw technology, specifically the instantaneous connections of electronic media, as bringing people all over the world together into a “global village.”20 He identified technology’s potential in completely transforming our ways of life, driven by the increasing popularity of television as a communication tool, something which Paik had picked up as well and emphasised in his own artistic practice. While Aguinaldo never formally studied technology, he did title a painting later that year Electricity Turned Off, Television Turned Off, Mind Turned On (fig. 6). The three “panels” transition from black to grey to “light,” implying the importance of conceptual thought in the electronic age. Though intrigued by McLuhan’s theories, Aguinaldo asserts one’s ability to be intellectually stimulated without the use of electronic media.

While Aguinaldo did not make any electronic media experiments of his own, he was at least to some extent “turned on” or even arguably “turned off” by technology, responding through the medium he knew best: painting. Like an abstraction in itself, this connection is inferred rather than explained.

II Inescapable Technology

In Malaysia, Choong Kam Kow felt similarly compelled to respond to technology through his artistic practice. From a rural background in Ipoh, Choong ventured abroad to train in fine arts in Taiwan for his BFA and at the Pratt Institute in New York for his MFA under a Fulbright scholarship.21 He lived in New York for four years from the mid-1960s, studying and exhibiting as well as teaching art at an international school.22

During his time in New York, Choong was exposed to recent trends in geometric abstraction—abstraction emphasising geometric shapes—and Minimalism, a movement emphasising seriality and the use of industrial materials in art making.23 He also observed that the modern, industrial world—meaning New York, but elsewhere that was industrialising too—“was predominantly shaped by a geometric structure and objects from architectural structure to commercial packaging.”24 In one article, he is quoted as saying: “The gradual development of my work towards the ‘hard-edge’ has been the result of personal reactions to my New York experience. New York reflects the inescapable technology that faces man.”25 “Hard-edge,” meaning delineated spaces of pure colour, was to Choong the visual correlation of technology and the seeming precision which it implied.

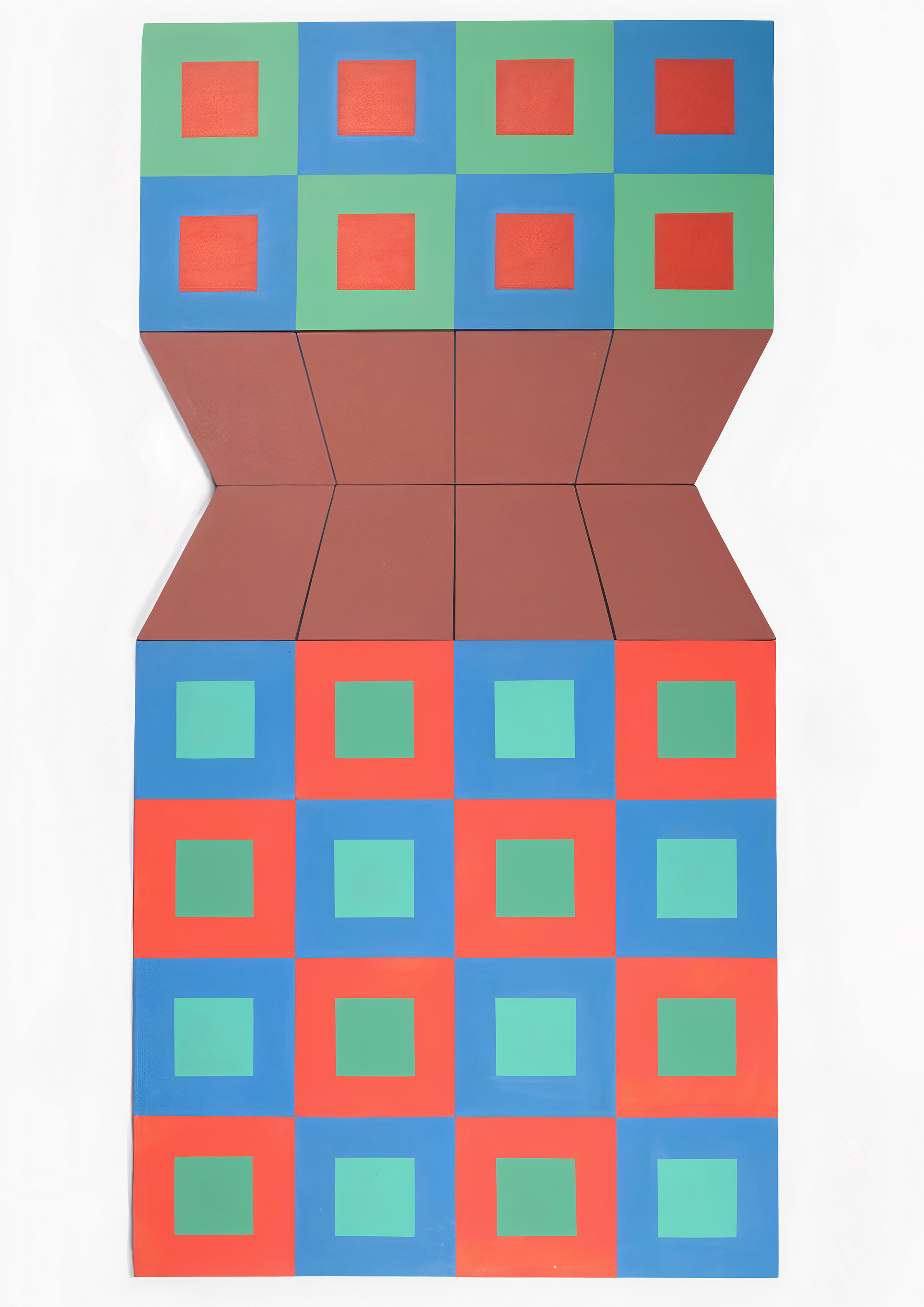

He developed this style further when he returned to Malaysia in 1969, joining the New Scene group of artists, who stressed an intellectual approach to art making.26 Malaysia at the time was aspiring to be an industrialised nation, after having achieved independence from the British in 1957, and Choong sought a painting form that expressed this ambition. He started his Shaped Canvas series, emphasising the inseparable relationship between space, colour and form. A pattern of colours in geometric shapes is applied in a smooth and flat finish onto a shaped canvas to achieve an object presence for the painting in the space, as in the aptly named Projection (fig. 7). This painting features alternating squares within squares of blue, red and green, joined by mirroring darker red trapezoids outlined in black. The painting appears to jut out from the wall, seemingly pressing into the space of the viewer. The scale of the work and the selection of colour was paramount to this effect. Choong believed in the power of colour, and emphasised this to his students at the MARA Institute of Technology in Shah Alam, where he taught for two decades.27

Unlike the earlier forms of abstract painting in Malaysia popularised by artists such as Syed Ahmad Jamal, Choong’s series concentrates on exactitude and logic rather than gesture and emotion. Choong considered this calculated form of abstraction, similar to Aguinaldo’s Linear series, as a fitting artistic representation of the modern apparatuses pervading the nation’s cityscape. It was impersonal and machine-like, yet still had the vestiges of traditional fine art through being rendered by hand. There is productive friction between the work’s mechanical appearance and the human application of paint. As the art writer Bintang states, “the combination of elementary geometric forms repeated in most of the canvases created a dynamic tension intended to symbolise the technological world of today.”28

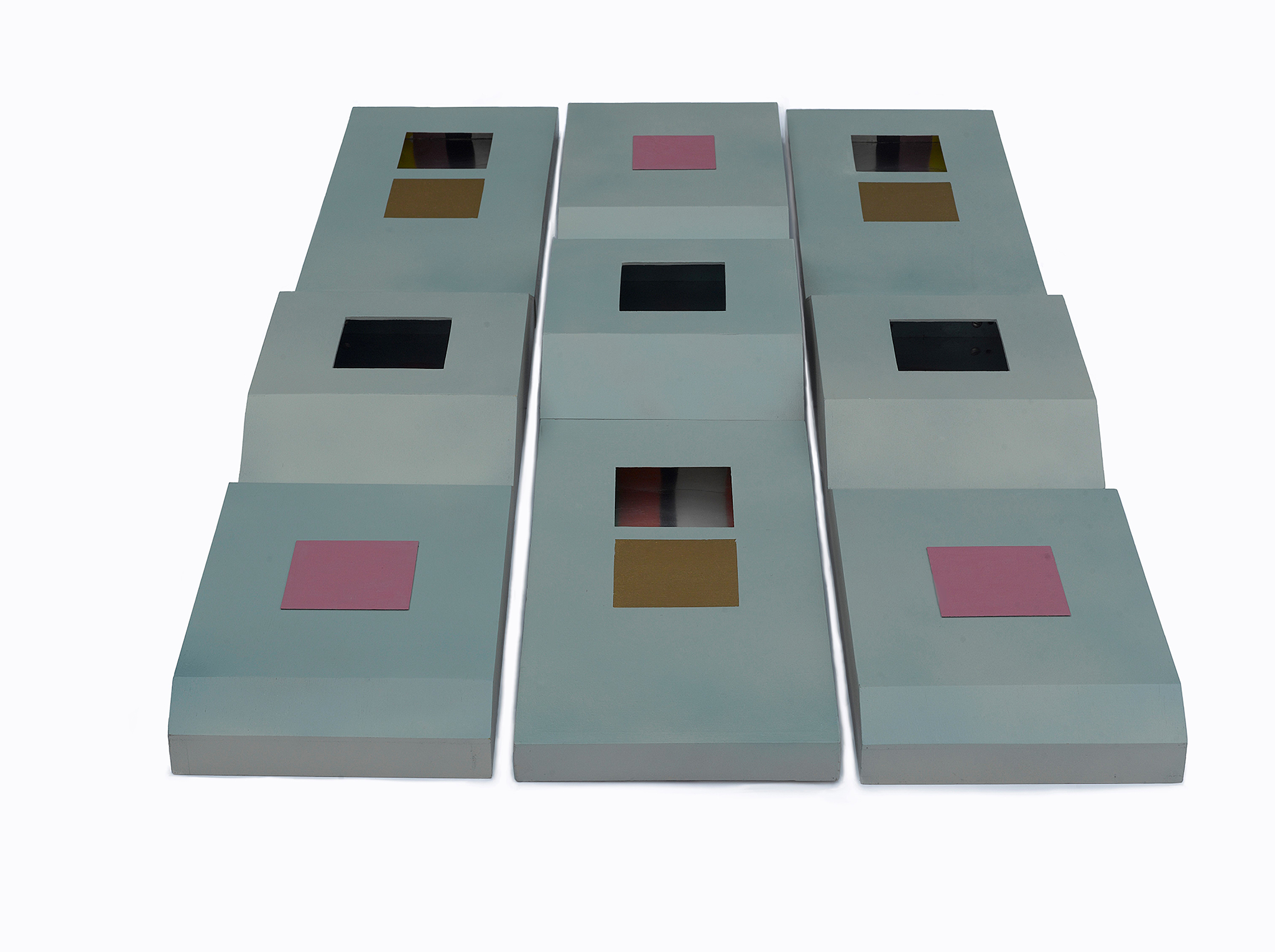

Dissatisfied with mere illusion, and with a desire to provide even more of an object presence to his artworks, Choong followed his Shaped Canvas series with the SEA Thru group of works in the early 1970s. SEA Thru was a simultaneous reference to the artist’s new residence in SEA Park in Petaling Jaya, to the region of Southeast Asia, and to being able to “see through” the artworks in this series.29 This group of works is made of multiple elongated painted sculptures with cut rectangular holes which viewers can peer into. Either mounted vertically on a wall or placed horizontally on a plinth, the works invite viewers to look into the holes to see the aluminium surface extending the painting rendered on the inner sides of the work through its reflected image.30 One example is SEA Thru—Harmony (fig. 8a), which has multiple thick stripes of colour within its cut-out space (fig. 8b). These colour bars might even be a playful, albeit unconscious, reference to the colour bars used to calibrate television screens. Though colour television in Malaysia only began transmission in 1978, Choong likely encountered it during his time in New York.31 More intriguingly, the reflective surface of the aluminium captures the viewers themselves as they peer inside (fig. 8c). This effect functions as a kind of “live feedback,” as Choong believes that when viewers see their own reflection, they would be encouraged to be more curious about the work and to look at it—and in it—further.32 This immediacy was a way to provide audience engagement and appeal.

Choong’s interests later shifted to nature, tradition and cultural values; his forms and lines became correspondingly softer, his colours blurred and overlapping. Eventually, the figure returned to his art practice. Yet in his earlier Shaped Canvas and SEA Thru series, rigidly structured abstraction served his intention of responding to technology and its inescapable presence at the time, through mimicry of machine application and of the instantaneity television offered.33

III A Transformation of Ideas

The artist who perhaps most overtly connected abstract art to technology is the Singaporean Lin Hsin Hsin. Lin trained in music, was academically schooled in mathematics and computer science, and studied painting under established artists Liu Kang (1911–2004) and Cheong Soo Pieng (1917–1983).34 She worked as a systems analyst while regularly exhibiting in solo and group shows.35 From the outset, Lin did not see a divide between art and technology, quipping in one article: “Why should I have to choose between painting and computers? Why should I cut off one arm when I can use both?”36

P.K. Toh, who wrote the catalogue for Lin’s first solo exhibition at Alpha Gallery in 1973, took immediate notice of her curious background, mentioning her training in these seemingly disparate fields and how they may have informed her practice: “Indeed Art, Mathematics and Music have one commonality—abstractness.”37 Abstraction was Lin’s preferred modus for painting and collage work and overlapped with her wider interests. She herself defined abstraction as a “transformation of ideas, the way the artist sees it,” a visual manifestation of the artist’s concepts or, as she described the topic of one of her talks, “human thought as art form.”38 Moreover, abstraction was not only a prevailing trend in art at the time but is also part of the world of computer science, as a “process of simplifying and hiding detail to get at the essence of something of interest.”39 McLuhan himself noted as far back as 1964 that “an abstract painting represents direct manifestation of creative thought processes as they might appear in computer designs.”40

Unlike Aguinaldo and Choong, the imagery in Lin’s abstract paintings is much more fluid. While Lin’s work has its share of straight lines, there are also curvilinear forms, biomorphic shapes and gradients of colour. This gives her paintings a sense of subtlety, whimsy and conjecture. Her works Distillation of an Apple (1976), imagining the tasks of a central processing unit, and Man Machine Dialogues (1984), on the Lotus software known for its spreadsheet application, both resemble cellular images under a microscope.41 Though Lin’s science training is in computers, the conscious or unconscious reference to the life sciences impresses a perception of harmony and wonder, rather than a rift and tension, between life and technology. For Lin, technology is not a threat but actually a creative field in itself. She even finds “elegance in how code can be written.”42

The human element is apparent in Lin’s work through rough edges, wispy lines and frisky composition—she does not try to mimic a machine in her application nor in her visualisations. There is no clearly observable formula. In her work Computer as Architect (1977), for instance, soft, thin vertical lines are spaced evenly in the background but are clearly hand-drawn. Flat three-dimensional models float in space like complex puzzle blocks captured in mid-air. Dark green rhomboids at the left and at the lower part of the arrangement disrupt any systemic array. In another painting, New Waves (c. 1984), the black angular form at the lower right also provokes a similar surprise.43

This is not to say that the artist’s works are improvisatory and uncontrolled. In fact, the writer Carol Lim described just the opposite: “As with programming a computer, her paintings and collages are carefully planned out in advance with a number of preliminary drawings and sketches.”44 Lin herself also iterated that in both the fields of art and science, one must exercise consistency as well as discipline.45

Over the years, while also exploring her interest in music and nature, Lin continuously returned to science and technology as a subject for her art. This is indicated clearly in the titles of her works: Systems (1972), Quaternion (1978), Spectrum (c. 1982), Eight Screens with Computer (1972) and several works in the 1990s which pun on IT as the acronym for Information Technology, such as IT’s Happening! and This is IT!46 Certainly, apart from titles, there are visual cues in the works themselves, such as a resemblance to chips on a circuit board in Network Communication (c. 1984).47Perhaps those most able to appreciate the visual and conceptual relationship between image and subject would be those as deeply versed in technology as the artist herself.48

Yet in 1994, technology merely as subject had reached its creative limit for Lin and was no longer sufficient.49 Technology needed to fuse more tightly with her art practice to be part of its actual method as well. In anticipation of the growing presence of the internet, Lin launched her virtual art museum in cyberspace and forsook traditional painting techniques.50 She turned to creating art using a mouse and, in more recent years, utilising a touch screen.51 Even though this application of digital devices seems to mark a change in her practice, her earlier work in painting reveals that her interest in technology was present from the start.52

Coda: Art and Technology in Colour

In Lin’s 1994 exhibition catalogue, the art historian T.K. Sabapathy wrote, “the relationship between art and technology […] has not been explored and developed by artists in Singapore and, for that matter, in the region of Southeast Asia—At least not in a continuous, strategic way in their practices; this is telling, as technology is the most pervasive and dynamic force in developing countries in this region.”53

Indeed, technology in Southeast Asia, like in other parts of the world, exerts a powerful influence, then and now. Yet, from the 1950s to the 1980s in the post-war era, electronic equipment, whether it be television, video, computers or the like, was naturally difficult to procure for pure artistic use and exhibition. Artists turned to other ways to respond to technology—abstraction, then a thriving trend, among them. With immense control but without the burden of objective representation, artists such as Aguinaldo, Choong and Lin demonstrate this link through their practice.

This essay illustrates only one of many possibilities in enriching the histories of art and technology in the region beyond the obvious medium-specific studies. While there is merit in research that focuses exclusively on artists’ actual use of electronic media, there is likewise value in also recognising artists’ interests in them vis-à-vis the very real-world practicalities of implementation and access, particularly at a time when the nascent nations of Southeast Asia were developing. Moreover, apart from the medium used, artists could also vary widely in their positions on technology, ranging from curiosity to anxiety to absolute delight. It may very well be that we should view this complex field of art and technology as Choong taught colour. As his former student, the artist Hasnul Saidon, recounts, “colours, [Choong] reminded, are a phenomena of light, never stay, never fixed, always intersecting, reflective, absorbing and emitting in different frequencies.”54

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank her PhD supervisor, Dr Erika Balsom, for her invaluable feedback to this essay and Jojo Gatbonton for the discussion on Liborio Gatbonton’s work.

- Christine Mehring, “Television Art’s Abstract Starts: Europe circa 1944-1969,” October 125 (Summer 2008): 29–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40368511 (accessed 31 May 2021).

- Ibid., 32–7, 40–5.

- Ibid., 36–7, 40.

- In his book Beyond New Media Art, Domenico Quaranta outlines the problematics of the term “new media art” and the varying definitions and positions of scholars, critics and artists in relation to it. Domenica Quaranta, Beyond New Media Art (Brescia: Link Editions, 2013), 23–41. See the rest of his book for his discussion on new media art in relation to the contemporary art world. Edward A. Shanken also emphasises the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in understanding art, science and technology. Edward A. Shanken, “Historicizing Art and Technology: Forging a Method and Firing a Canon,” in Media Art Histories, ed. Oliver Grau (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 65–6.

- For example, for works made on video, this started in the Philippines in 1972 with the work of Johnny Manahan. In Thailand, this was in the mid-1980s with the video works of Apinan Poshyananda. In Indonesia, Krisna Murti, Heri Dono, Tenguh Osterink and Arahmaiani have been identified as developing early new media art in the 1980s and 1990s. Artists started using video as medium in Malaysia in the 1980s, following the computer-generated collages of Ismail Zain. Clarissa Chikiamco, “Johnny Manahan: Making ‘Marks’ and Leaving ‘Evidences’: The Art of Johnny Manahan 1971-82,” in A Fact Has No Appearance: Art Beyond the Object, eds. Clarissa Chikiamco, Russell Storer & Adele Tan (Singapore: National Gallery

Singapore, 2016), 21. See also Steven Pettifor, “Video Art in Thailand,” in Video, An Art, A History: A Selection from the Centre Pompidou and the Singapore Art Museum Collections, eds. Francis Doral et. al. (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2011), 56–7; Edwin Jürriens, Visual Media in Indonesia: Video Vanguard (New York: Routledge, 2017), 153; Hasnul J. Saidon & Niranjan Rajah, “From Mass to Multimedia: Malaysian Art in an Electronic Era,” in Reactions—New Critical Strategies: Narratives in Malaysian Art, vol. 2, eds. Nur Hanim Khairuddin & Beverly Yong with T.K. Sabapathy (Kuala Lumpur: RogueArt, 2013), 222–4, Saidon & Rajah’s original essay was published in Malay in the exhibition catalogue Pameran Seni Elektronik Pertama [First Electronic Art Exhibition] in 1997. - “In This Issue with Mobilways,” Mobilways 3, no. 4 (April 1958): unpaginated. Accessed via Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Digitized Archives ART IX, 207, courtesy of Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation.

- Purita Kalaw-Ledesma & Amadis Guerrero, The Struggle for Philippine Art ([Manila]: Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, 1974), 14–5.

- Rod. Paras-Perez, Edades and the 13 Moderns (Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1995), 12–3.

- Ramon R. Tuazon, “Philippine Television: That’s Entertainment,” National Commission for Culture and the Arts, https://ncca.gov.ph/about-ncca-3/subcommissions/subcommission-on-cultural-disseminationscd/communication/philippine-television-thats-entertainment/ (accessed 7 June 2021).

- Magtanggul Asa [Aurelio Alvero], The First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagala (Pasay City: House of Asa, [1954]), 1.

- Albert Abramson mentions that the “quality of television images in 1948 […] was considered to be roughly equivalent to 16mm home movies, although actually somewhat better with reference to contrast and detail.” Albert Abramson, The History of Television, 1942 to 2000 (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 27. Colour television started in the Philippines in 1966 so at the time the cartoons were published, television was still black-and-white. See Mario Alvero Limos, “ABS-CBN’s Historic Milestones Through 70 Years of Service to the Filipino,” Esquire, 6 May 2020, https://www.esquiremag.ph/long-reads/features/abs-cbn-history-and-milestones-a00293-20200506-lfrm2 (accessed 16 July 2021); entries on interference, raster, video noise in Keith Jack & Vladimir Tsatsulin, Dictionary of Video and Television Technology (Oxford: Newnes, 2002), 154–5, 228, 303.

- Alice M. L. Coseteng, “Art International,” The Weekly Graphic, 18 August 1965, 28, in Philippine Modern Arts and Its Critics, ed. Alice M.L. Coseteng ([Manila?]: Unesco National Commission of the Philippines, 1972), 43.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Emmanuel Torres, “Nationalism in Filipino Art ‘Hot’ and ‘Cool,’” Esso Silangan XIV (4 June 1969): 9–10, 15, in Coseteng, Philippine Modern Arts, op. cit., 171.

- Ibid.

- Ma. Victoria Herrera, “Insider/Outsider: Revisiting Lee Aguinaldo,” in The Life and Art of Lee Aguinaldo (Quezon City: Vibal Foundation, 2011), 53.

- Op. cit., 45–6.

- Cultural Center of the Philippines Library and Archives.

- Marshall McLuhan, Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1962), 31.

- Pok Chong Boon, “Contemplating Colours, Shapes and the Dimension Beyond: The Evolution of Dr Choong Kam Kow’s Conceptual Configurations,” in Retrospective Choong Kam Kow: Cross Culture Trans Era, ed. Haned Masjak (Kuala Lumpur: National Visual Arts Gallery, Malaysia, 2014), 110, 112, 114.

- Op. cit., 110, 112.

- Ramlan Abdullah, “Journey Remembered, Trading Imagination, Series and Processes,” in Masjak, op. cit., 24.

- Choong Kam Kow, online interview by the author and Goh Sze Ying, 31 August 2020.

- Bintang (Siti Tengku Zubeidah), “Children’s Art Show to Run 4 Weeks,” Sunday Mail (Malay Mail), 1 March 1970, 12. With thanks to Choong Kam Kow.

- T.K Sabapathy, “Introduction,” in T.K. Sabapathy & Redza Piyadasa, Modern Artists of Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Ministry of Education Malaysia, 1983), 20.

- The school is now known as University Teknology MARA or UiTM. Hasnul Jamal Saidon, “Guru,” in Masjak, op. cit., 158.

- Bintang, op. cit.

- Pok, op. cit., 120; U-Wei bin Haji Saari, “Choong Kam Kow: A Few Things Students Knew About Him,” in Masjak, op. cit., 175.

- There is at least one picture of a SEA Thru work mounted directly on the floor without a plinth, likely See Thru—Flow 3 in the collection of Balai Seni Visual Negara, as seen in Senilukis Malaysia—25 Tahun [Malaysian Art—25 Years] (Kuala Lumpur: Balai Seni Lukis Negara, 1982), unpaginated. Pok also discusses the works not needing a pedestal in Pok, op. cit.,122. The artist has clarified directly that the SEA Thru works, when displayed horizontally, are meant to go on a plinth to enable visitors to properly look inside the works.

- For the advent of colour television in Malaysia, see Hashim Awang & Wan Abdul Kadir Yusof, “Cultural Aspects of the Information Revolution in Malaysia,” in The Passing of Remoteness?: Information Revolution in the Asia-Pacific, eds. Meheroo Jussawalla, Dan J. Wedemeyer & Vijay Menon (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1986), 145. Choong was living in New York when television networks in the USA started to fully convert to colour in 1966–1967, see Susan Murray, “‘Never Twice the Same Colour’: Standardizing, Calibrating and Harmonizing NTSC Colour Television in the Early 1950s,” Screen 56, no. 4 (Winter 2015): 434.

- Choong Kam Kow. “Study for SEA Thru—The Spirit Behind the Stripes.” Undated. Collection of the artist.

- Choong also returned to technology as subject in his later Co-Exist series from 2003. While also abstract, they have a more playful feel with more layering of images and even incorporate QR codes. This also reflects a shift in his attitude to technology. Choong Kam Kow, “The Co-Exist Series”, https://www.choongkamkow.com/the-co-exist-series.html (accessed 15 July 2021).

- P.K. Toh, “Note on the Artist,” Lin Hsin Hsin ([Singapore]: Alpha Gallery, [1973]), unpaginated. Tan Ee Sze, “Tempering IT with Poetry,” The Straits Times, 15 October 1992.

- Bibiana Choo, “Balancing Art,” Business Times, 21 July 1980, 7, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/biztimes19800721-1.2.20.3 (accessed 13 January 2022).

- Carol Lim, “Hi-Tech Images on Canvas,” The Straits Times, 16 September 1984, 8, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19840916-1.2.48.11.1 (accessed 13 January 2022).

- Toh, op. cit.

- Lin’s definition of abstraction is as quoted in Michael Chiang, “Just as Good with Numbers,” New Nation, 18 July 1980, 27, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/newnation19800718-1.2.80.1 (accessed 13 January 2022). The quote from her talk is from “Artist’s Talk on Thought as Art Form,” The Straits Times, 11 August 1987, 13, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19870811-1.2.27.12 (accessed 13 January 2022).

- Sally A. Fincher & Anthony V. Robbins, The Cambridge Handbook of Computing Education Research (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 526.

- Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: Extensions of Man (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994), 8. This is a reprint from when it was first published in 1964.

- This information was provided in the artwork labels of the artist’s recent exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore, Lin Hsin Hsin @Speed of Thought, a part of the larger show Something New Must Turn Up: Six Singaporean Artists After 1965, held in 2021. Lin’s exhibition was curated by National Gallery Singapore senior curator Adele Tan.

- Tan, op. cit.

- Lim wrote of this work, “Just as the viewer begins to be lulled into complacency by the fact that everything appears to be going according to plan, he is shaken out of his reverie by a bold, flying black form in the lower right side of the canvas. It is followed by a painstakingly drawn half-moon shapes which seems to have no business being there but works, compositionally, just the same.” Lim, op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Chiang, op. cit.

- Lin Hsin Hsin, Lin Hsin Hsin: Work from Art, Science & Technology Series (Self-pub., 1994).

- Grace Yu, “Hsin Hsin Takes a Detached View,” Business Times, 17 September 1984, 8, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/biztimes19840917-1.2.18.3 (accessed 13 January 2022).

- Quaranta discusses the importance of the art world to have media literacy and conversely, those from “new media” to be familiar with art history. Quaranta, op. cit., 216–9.

- Exhibition text of Lin Hsin Hsin @Speed of Thought.

- “First local art museum in cyberspace launched,” Business Times Singapore, 20 April 1995. Exhibition text of Lin Hsin Hsin @Speed of Thought.

- Exhibition text of Lin Hsin Hsin @Speed of Thought. Janet Ho, “She Paints with a Mouse,” The Straits Times, 28 November 1997; Lin Hsin Hsin, “Finger Painting -- Bootstrapping and Articulating Finger Haptic I/O on a Touchscreen,” in 2016 20th International Conference Information Visualisation (IV) (Lisbon: Portugal, 2016), 404–7, doi: 10.1109/IV.2016.76.

- It may also interest the reader to know that Lin is also a poet and has also written poetry on technology as well. See Tan, op. cit.

- T.K. Sabapathy, “Revealing and Concealing: The Painted World of Lin Hsin Hsin,” in Lin, op. cit., 13.

- Saidon, op. cit.